In What Sense is Matter 'Programmable'?

Just as every smartphone app was latent in the laws of computation as laid out nearly 100 years ago, what lies latent within the laws of physics, and how might we use this to increase our control over physical matter?

- An analogy to get us started:

- The Obvious

- The Quantum Obvious

- Synthetic Biology and ‘Active’ Matter

- Physical neural networks and The Manifold Hypothesis

- Drexlerian Nanotech and Von Neumann’s Universal Constructor

- Exotic phases and weird physics

- Conclusion

David Deutsch, described aptly by Tyler Cowen as a kind of “philosopher of maximal freedom” famously points out that any state of the universe that is not explicitly prohibited by the laws of physics, is therefore realisable by some set of physical transformations using those laws. The gap between our current state and that unrealised-but-possible future state is a gap in our knowledge. In this way, Deutsch elevates ‘knowledge’ to a kind of fundamental force in the universe. Our ability to create useful explanations about the physical world increases our knowledge, and by increasing our knowledge we are able to access more possible states. In a Deutschian sense, the only reason humans can’t currently live for hundreds of years isn’t because it’s prohibited by the laws of thermodynamics (it’s not!), it’s because we lack the requisite knowledge to apply the correct physical transformations to matter that would prolong our lifespans.

Deutsch’s distinction between discovering and describing the laws of the universe (the job of theoretical physicists as currently understood), and enumerating the possible realities contained within (or allowed by) those laws, hints at a broader conception of physics: the physics of the possible. By simply asking what constraints there are on a system, or in what ways we can not violate those constraints, we can uncover the true richness contained therein. This post is an exploration of the constraints of physical matter, and in what ways it is ‘programmable’.

An analogy to get us started:

By the mid 1930s, Alan Turing and Alonzo Church had formalised every detail of computation as we now understand it. The mathematics of the Universal Turing Machine (UTM) was complete - as grand unified theories go, it was a knockout. We can imagine the Turing Machine as a kind of ‘universe’ - let’s call it the UTM-verse. Like our own universe, the UTM-verse is complete with a set of laws. Want to go faster than light in our universe? Too bad - against the law. Want to write a programme that decides if another program halts in the UTM-verse, too bad! Against. The. Law! But even though we had the exact laws pinned down since the ’30s, it took another 76 years for somebody to create Tinder and instantiate it on a Turing Machine1. Why the delay? Did we need a revolution in computer science between Turing and Tinder in order for it to be born? Clearly not! Tinder was always theoretically possible within the known laws of computation but, in a Deutschian sense, it required an act of creativity to conceive of the set of transformations within those known laws that were required to instantiate it.

So now that we appreciate that knowing the laws that govern a system doesn’t tell us about all the cool things we can do with those laws, let us consider the ways in which matter might similarly be ‘programmable’. Here I mean programmable in two senses:

- ‘Programmable’ as an analogy to the above spiel about computer programs - i.e. as a system which, if we knew its fundamental laws, would still contain interesting phenomena if we had the creativity to use those laws in novel ways

- ‘Programmable’ as in literally we could give ‘instructions’ to matter, and like a Universal Turing Machine, it would be able to interpret or follow those instructions, carrying out either literal computation, or just reorganising itself according to some ‘program’

The Obvious

Trivially, every Universal Turing Machine must be instantiated in the matter of our physical universe if it is to do any computing. The original Turing Machine was proposed as a kind of Platonic mathematical entity, consisting of an infinitely long tape with symbols inscribed at interval which instructed the machine on what action to take next. Unfortunately, big as the universe may be, infinitely long tapes aren’t practical. Thankfully, we are lucky enough to live in a universe where we can make perfectly good approximations to the UTM - no tape required!

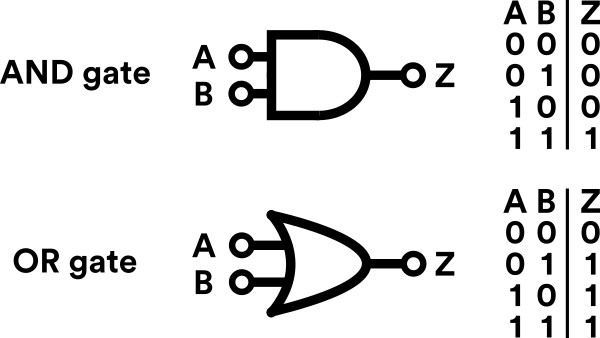

So the mathematics governing computers and computer programming is realisable within our universe, which means that the atoms that comprise whatever system we use to emulate the UTM are in some sense ‘programmable’ matter. Each electron in the transistors of your computer is obeying simple laws of physics, and the movement of those electrons alters its physical properties so that it acts like a switch which is in one of two binary states, and from that simple binary switch you can build little logic circuits that compute ‘AND’ or ‘XOR’ or ‘NAND’, or any combination thereof. And, somewhat surprisingly, all of those, when strung together, is enough to create all of the approximate Turing Machines you use and love. So physical matter is programmable. Neat!

As it happens, a lot of things are Turing-complete (able to simulate any other Turing Machine). Some are obvious (your laptop, smartphone), but many are less so: Microsoft Powerpoint is Turing complete, meaning you could (albeit inefficiently) do any computation in Powerpoint, including build the Apple OS! Cellular automata are also Turing complete, as is Factorio! From a physics point of view, we know that we can encode a Turing Machine in a 4-dimensional manifold, but also that computing certain facts about that manifold are then undecidable by that Turing machine! There are also interesting properties about the computational power of fluids (i.e. can the flow of water ‘compute’ something in a meaningful way?), and this has implications for long-unsolved questions about the Navier-Stokes equations!

The Quantum Obvious

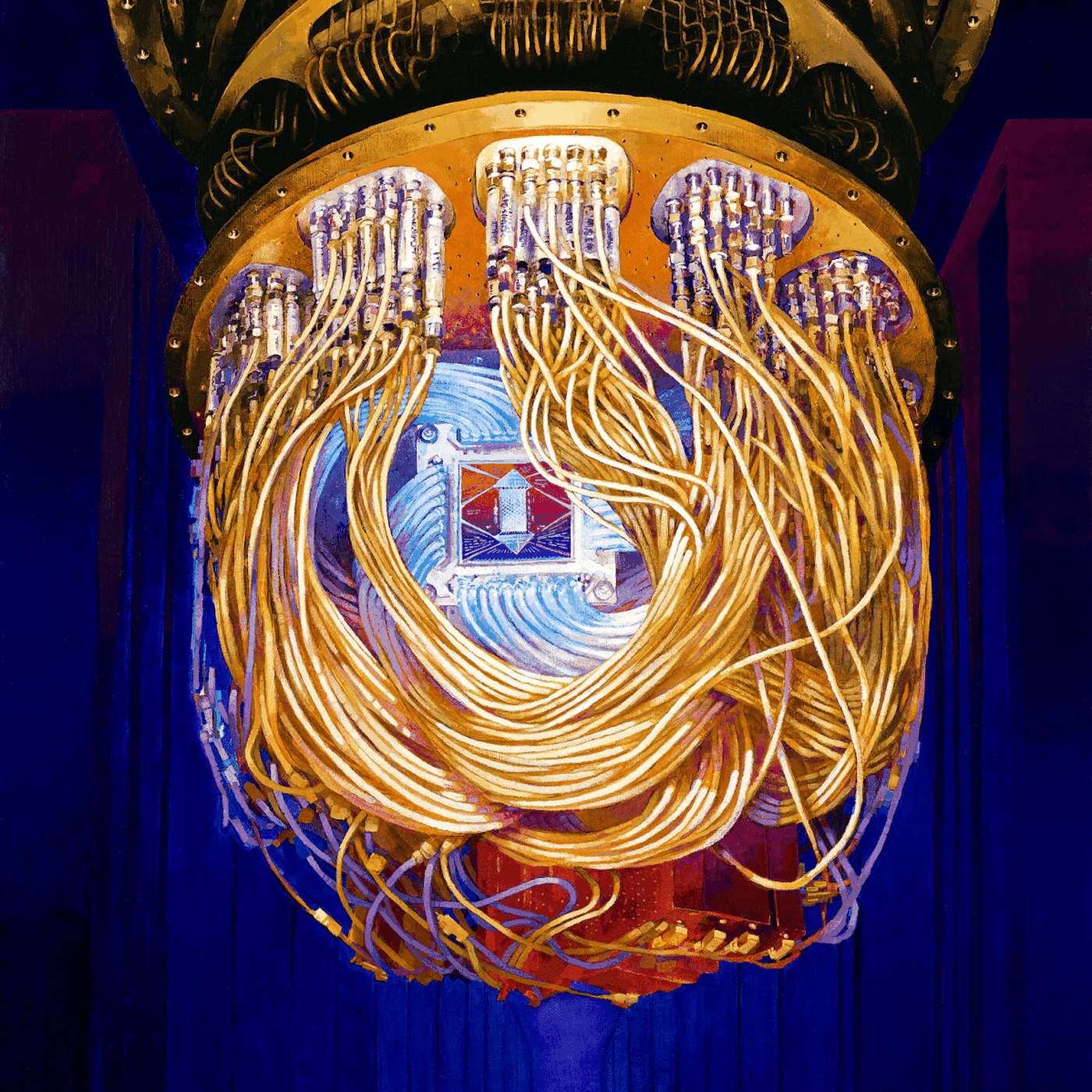

side note: I propose quantum computers are our most gorgeous-looking technology and we should celebrate this more

Quantum computers are also going to have to run in our physical universe! And so far, besides a few algorithms, the thing they might be most useful for is simulating the behaviour of quantum systems. Actually, if I’m careful not to just gloss over this, this feels really surprising. Try to seriously internalise for the moment that reality really is quantum mechanical. Not just abstractly know it’s true in textbooks, but like everything you see is some excitation of a quantum field. It feels pretty weird to think that you can take some of those excitations, couple them together, make some of the excitations (e.g. a photon or an electron) behave as ‘qubits’ which have a state which can be used to store computational information (e.g. the ‘Up’ or ‘Down’ spin states of the electron), and then you can use that computational state to build a simulation… of excitations… in a quantum field … like the spin of an electron… or the phase of a photon…

Aaaanyway…

Quantum Computing

It’s important to acknowledge that quantum computers aren’t more general than classic computers, but for certain things, they’re remarkably more efficient! So everything you can do with a quantum computer, you can simulate in a classical computer, given enough time/memory (what did you think the ‘Universal’ in ‘Universal Turing Machine’ was for?).

this lovely diagram is from this Simon's Foundation report

Digging into the strange hall of mirrors situation of reality simulating reality that is quantum computing seems a worthwhile diversion right now if we are to dig into the question about programmable matter. So let’s do a whirlwind tour of quantum computing so that we can point out some intriguing points:

A quantum system has a number of ‘base’ states. Let’s use the spin of an electron, which can be either ‘spin-up’ or ‘spin-down’. Now that’s a nice two-state system, rather like the on-off ‘bit’ which we’d use in normal computing.

Let’s represent the spin-up state as the vector and the spin-down state as If we call the whole quantum state $|\psi\rangle$, then we can2 represent that state as a linear combination of these two base states (a superposition, if we’re feeling cool):

where $\alpha$ and $\beta$ are just coefficients telling us ‘how much’ of the ‘up’ or ‘down’ states we want in our total state. Now earlier we said we built up our remarkably general Universal Turing Machine with just combinations of ‘logic gates’ - things like the ‘AND’ gate, which returns ‘1’ if both its inputs are ‘1’, and ‘0’ in all other cases

Turns out we can represent these logic gates as matrices. Let’s look at the ‘NOT’ gate - the ‘NOT’ operation just flips a zero to a one and vice versa. So we want NOT(‘spin-up) to equal ‘spin down’. Let’s call the operator doing this $X$. We want $X$ acting on to give The matrix which achieves this is

and we can verify with normal matrix multiplication that:

But shouldn’t it be really interesting and weird to us that we can make matter itself ‘act’ like the matrix (If that one doesn’t impress you then imagine a more complicated set of operations on qubits until you’re sufficiently impressed). I think some would say I have this exactly backwards and that matter is just doing its thing, and we’re finding ways in which that is approximately like the matrix

Putting that aside, it’s still intriguing to think that we have this mathematical formalism that describes quantum mechanics, and we can use quantum reality to ‘act out’ computations of that mathematical formalism. It’s apparently still unknown whether every possible physical system can be simulated in a quantum computer. David Deutsch certainly seems to think so3:

I had thought for a while that the quantum theory of computation is the whole of physics. The reason why it seemed reasonable to think that was that a universal quantum computer can simulate any other finite physical object with arbitrary accuracy, and that means that the set of all possible motions, which is computations, of a universal computer, corresponds to the set of all possible motions of anything. There is a certain sense in which studying the universal quantum computer is the same thing as studying every other physical object. It contains all possible motions of all possible physical objects within its own possible diversity.

Now as it turns out, there are many different ways we can build physical versions of our quantum computers. But in each, we try to set up some special circumstances where the annoying noise of the larger physical world doesn’t disturb our delicate quantum state so that we can use the quantum properties of matter to do computations like those above. This ability to change the informational content of matter sure feels like ‘programming’ matter to me.

Interested in quantum computing? You can’t do better than this intro by actual expert Michael Nielsen at quantum country

Synthetic Biology and ‘Active’ Matter

Breaking from the abstract world of computable functions for a bit, let’s look at biology - nothing’s ever been complicated there, right?

Going back to the analogy we started this post with - the space of all possible computer programs enabled by the laws of computation - what about the space of all possible organisms? This ‘space’ is interesting because there’s another actor in play - evolution by natural selection. Whereas the space of possible physical systems is something we “anthropic-principle” our way into, and the space of computer programs is something we as humans have been steadily exploring through acts of software creativity, the space of possible designs for biological creatures has been steadily explored by evolution for the last few billion years. Clearly the principles by which ‘eyes’ might work were not just possible within the laws of physics, but they’re possible within the narrower scope of the rules of biology and evolution. One of our species’ goals should be to explore more of the landscape of possible organisms!

Why speak of biological matter as ‘progammable’?

Cells can receive inputs, make calculations based on them, and output signals based on those calculations. Seems like a pretty decent computational system to me. This is true whether we’re thinking of neurons, or more general cells we don’t readily associate with computation. Synthetic biology is concerned with the ways in which we can intervene in a cell (or network of cells, or some other scale of the biological system) and shape the trajectory of the intricate cellular machinery to achieve a desired function or output.

A simple example of using biology to achieve ‘programmable’ matter is using genetic engineering to insert the gene for insulin into a bacterial cell. That gene acts as a template which can be transcribed into the insulin peptide, which we can purify and use to treat insulin-dependent diabetes. That insulin-secreting bacterial cell feels a lot like the kind of thing I want to call ‘programmable matter’: a little slice of reality we can direct and control - reconfigurable matter with custom functions!

Enhancing our ability to program and control biological matter is an interesting avenue because biological systems generally have a few other interesting properties:

- Homeostasis - despite the dynamical flux of the world, biological systems tend to maintain many of their parameters within small ranges, despite perturbations. A laptop running your bootlegged copy of Sims 2 is fragile and static - delete one of the key lines of code and Sims won’t even open. Comparatively, the fidelity of DNA polymerase has an error rate of ~1 error per 100 000 nucleotides - meaning that per replicating diploid human cell (~6 billion base nucleotide pairs) there would be something like 120 000 errors. Clearly that isn’t the case, and the reason is because of DNA error correction and repair. The living cell has mechanisms to bring it back to the ‘set-point’ (in this case, the ‘correct’ genome for that organism). Living organisms tend to act, on themselves or their environment, in such a way that their key parameters are kept within viable ranges, whereas inert matter is subject purely to environmental degradation.

- Autopoiesis - which refers to a system’s capability to reproduce itself by creating its own components - is an especially intriguing ability for a programmable system to have. Biology is the story of self-replicating molecular machines and the control systems they build. Tapping into this ability unlocks novel regenerative, replicative matter. It’s also terrifying if either evolution or humans program these replicators for harmful purposes.

- Self-organisation - a single cell not only has all the computational abilities we’ve mentioned already, and the ability to execute almost arbitrary (DNA) code, but the cell can self-organise into functional forms of striking complexity, which is again, robust to perturbation. Think about trying to write the computer program that would generate a pair of lungs. You need to pave kilometers of tubing with cells, ensuring that there’s never a gap of more than 2 micro-metres between the airway and the capillary meant to ferry oxygen from it. And you need to do all of that in a non-static environment, responding to the movements of walking, breathing, growing. Programmable matter that can self-assemble intricate structures at both the molecular- and macro-level is a wild technology to even conceive of. The fact that it’s present and working in you right now is crazy!

So cells and living systems generally have these properties, in addition to being able to execute instructions we give them. Want two more reasons to find cellular computation exciting? Fine! 1) Biological computation is extremely efficient - as in several orders of magnitude more efficient than the best supercomputers. And 2) biological learning rules significantly outperform those used in artificial intelligence right now (another reason I’m so optimistic about architecture search and evolved AI-optimisers!) The synergistic possibilities of all this give us good reason to think the 2020s will be the decade of synthetic biology!

What aspects of biology are ‘programmable’?

Some readers may have noticed that I casually failed to distinguish between two very different ways of programming biological matter:

-

We can imagine the DNA of the cell as providing the instruction set for the cell, and by editing the DNA, we ‘program’ novel functions and outputs into the cell

-

We can send cellular signals by binding molecules to membrane receptors, the intracellular machinery of the cell can process this signal, and various outputs - in the form of up- or down-regulation, signal propagation, synthetic activity, etc. - can occur

But it’s worth lingering on the various ways we can ‘program’ biological matter, then, because each may be useful, and they’re just really cool.

Programming by DNA editing

Firstly, DNA and genetics seems more like a lookup table than a programming language. You specify a string ‘GTG/CAC/CTG/ACT/CCT/GAG’ and that gives you the sequence of amino acids ‘Val/His/Leu/Thr/Pro/Glu’, and that’s the first 6 amino acids in the beta chain of human haemoglobin. There’s also lots of secondary features in this ‘language’ like reading frames and post-translational and post-transcriptional processing, and which genes are available for translation at a given time, and how translation is promoted or inhibited. But the basic idea of ‘inject’ new code and use the molecular machines to assemble it isn’t far off.

Tools like CRISPR give us this kind of ability to edit the genome, but more excitingly, open the path to novel protein design (tools like AlphaFold will be crucial here, but also see Biological structure and function emerge from scaling unsupervised learning to 250 million protein sequences and Deep neural language modeling enables functional protein generation across families for some incredible ideas that aren’t as famous as AlphaFold!)

Programming by epigenome editing

One problem with editing the genome directly is that cells generally don’t like it when you cause breakages in their DNA. So instead of trying to remove a problematic sequence, why not just suppress it so that it’s never expressed? As it happens, cells already possess machinery that can inactivate genes like this - and these epigenetic modifications provide a nice platform for programming the cell. Enter a recent CRISPR modification called ‘CRISPRoff’ (yes, there’s also a CRISPRon) which uses the sequence-targeting ability of CRISPR to direct molecular machinery that can methylate (and thereby inactivate) almost any part of the genome. This is a big deal because the difference between your hepatic cells and your neurons are largely differences in which parts of their genomes are expressed at any given time, and so the ability to selectively turn expression on or off is a potential Hamming-Enabler for fine-grained control of complex multicellular-morphology (see later in this post).

Programming by cell signalling

At the cellular level, we can bind all kinds of ligands to cellular receptors to set off any of the signalling cascades that regulate and control the cell. Achieving a high degree of control of these complex pathways would be a key milestone in medicine and longevity. This is nicely addressed in ‘Morphogenesis as Bayesian inference: A variational approach to pattern formation and control in complex biological systems’:

most problems of biomedicine – repair of birth defects, regeneration of traumatic injury, tumor reprogramming, etc. – could be addressed if prediction and control could be gained over the processes by which cells implement dynamic pattern homeostasis.

Indeed, a tantalising possibility, realisable by ‘programming’ biological circuits, would be a new type of drug. A drug that isn’t a single molecule with a single pathway or target, but that is itself a kind of ‘programme’, capable of reacting to the state of the cell it’s acting on and implementing different functions depending on that cellular state. I got this idea from Arye Lipman on his Substack The Last Great Mystery, where he calls therapeutics like this ‘logical medicine’. If we start thinking of disorders like cancer (or even aging generally) as derangements of the complex dynamical systems implemented in cellular regulatory networks, then being able to recognise, react to, and correct these derangements would be a sigificant step towards treating these diseases.

Programming with bioelectricity

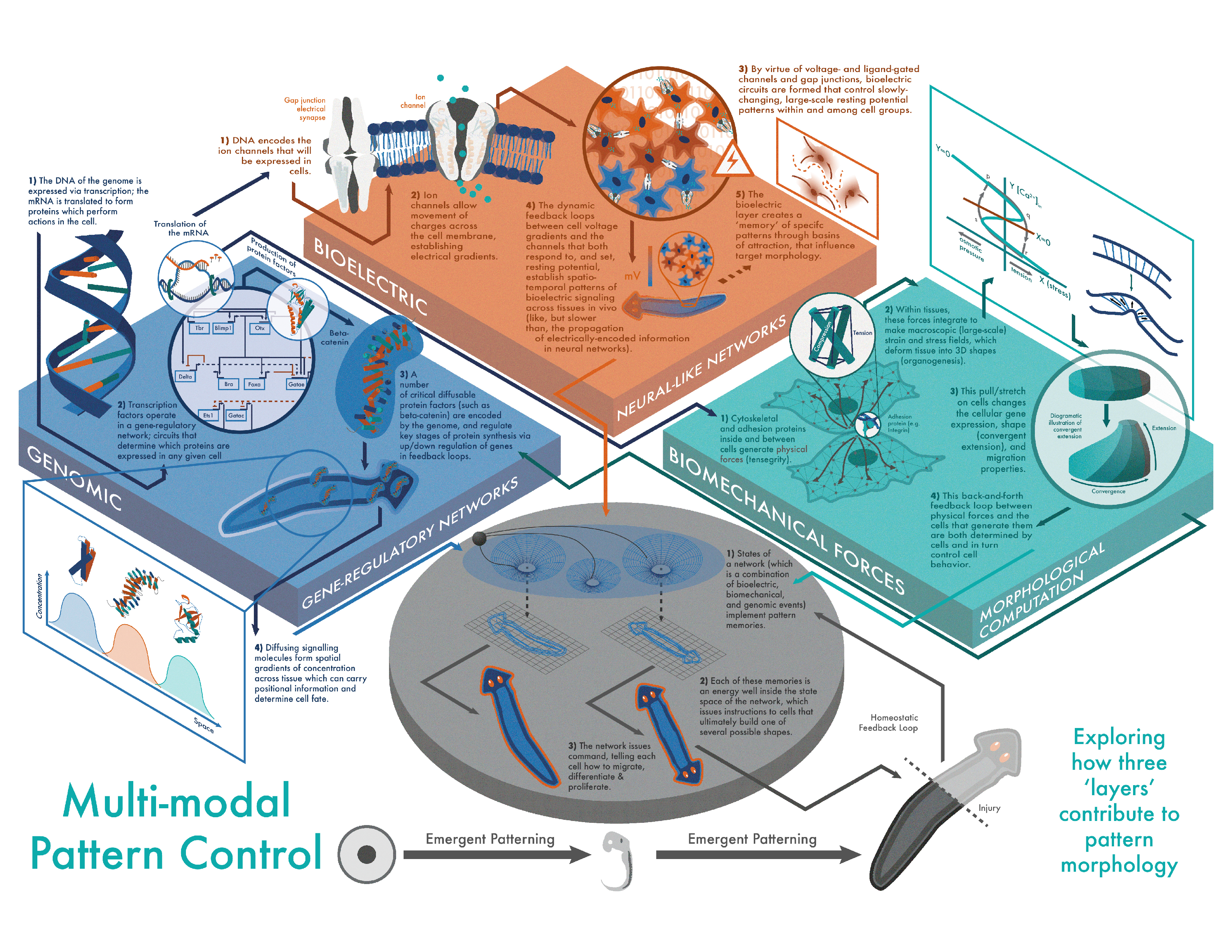

This gorgeous graphic by Ben Oldroyd for the Levin Lab

Cellular decision making is clearly reliant on more than just the cell’s genome (after all, every cell in your body has the same genome). Even if you account for different patterns of gene-expression between tissue types, we’re still left with unexplained fidelity in cellular morphological coordination. Enter biolelectricity! Turns out that simple physical variables like the charge-polarisation of cells can control wide-aspects of their morphology, and coordinate cells to adaptively achieve complex macro-scale objectives (like building an eye, or coordinating to make sure the right nerve cells make their way to that eye so that it’s usable). Oh, and there is increasingly awesome work by Michael Levin and colleagues that shows that if we intelligently intervene in these bioelectric circuits, we can alter key aspects of cell differentiation and proliferation.

Programming by training cell networks

Max Hodak on Twitter

I like the thrust of this tweet - given all of the properties of living systems we’ve already mentioned, this seems like a useful experiment to perform. As far as I can tell, if we can think of a clever way to encode ImageNet and pass it to a network of cells, and if we could read the output, then training can proceed by either something akin to the method in Deep physical neural networks enabled by a backpropagation algorithm for arbitrary physical systems. Or, if we take the predictive processing perspective, maybe we can use what we know about the neurobiology of prediction-error signalling to train our ‘network’. Programming a piece of ‘predictive-matter’ like this could be really useful to neuroscientists trying to study these networks, and maybe to AI-researchers looking to learn something from biological intelligence.

Programming complex morphology - the neural cellular automata perspective

We can also think of what we can achieve if we leverage the three distinct properties of living matter (homeostasis, autopoiesis, self-organisation) in our programmed cells. What complex morphologies are we able to create, and what functions can we realise? One frustrating possibility might be that evolved circuits are too complex for humans to intelligently engineer (and maybe this is a cryptographic defence mechanism). So does that mean the project of synthetic biology is doomed? I don’t think so.

Back in the Ye Olde Days of Good Old Fashioned AI, we thought that hand engineering features and encoding huge knowledge-bases was the key to intelligence. Nowadays, we’ve seen the power of just black-boxing the system and using a powerful optimiser to learn whatever complex function we desire. No one knows how to write explicit rules to differentiate Chihuahuas from muffins, but if we avoid explicit rules and just train some parameters in a neural net, we do just fine!

Andrej Karpathy extended this idea to coin the term ‘Software 2.0’, wherein he proposed a shift in how we create complex computer programs. Instead of explicitly programming each line of our app, we would specify an underlying architecture (a neural net), and provide it with some data which shapes its behaviour towards some desired functionality. I think we’ve seen early pieces of ‘software 2.0’ in some of the GPT-3 and OpenAI Codex demos.

So, if it does turn out that biology is too complex to ‘programme’ in the way we’re used to (the software 1.0/hand-engineered way), might we make progress with a kind of ‘Synthetic Biology 2.0’?

I first had a real ‘wow’ moment and began to think something like this may be possible after I saw the work on ‘Neural Cellular Automata’. Think about a standard cellular automaton, which has defined rules for how to update the grid, given its current state. In neural CAs, we learn the update rule, but more importantly, we learn a complex cellular ‘state’, which is analogous to the complicated cellular signalling cascades we’re imagining may be too complicated for humans to programme with directly. As the authors put it in ‘Growing Neural Cellular Automata’:

Hidden channels don’t have a predefined meaning, and it’s up to the update rule to decide what to use them for. They can be interpreted as concentrations of some chemicals, electric potentials or some other signaling mechanism that are used by cells to orchestrate the growth. In terms of our biological analogy - all our cells share the same genome (update rule) and are only differentiated by the information encoded the chemical signalling they receive, emit, and store internally (their state vectors).

Obviously, this is made much easier by not actually having to use real cells here, but I find the approach instructive. Don’t fuss around trying to understand all those internal pathways, just optimise the high-level objective4. I have spent some time thinking about ways that the ideas in Deep physical neural networks enabled by a backpropagation algorithm for arbitrary physical systems could be used to actually implement this kind of ‘black-boxing’ in cells, but so far haven’t made progress. Any comments with ideas here or links to work that might enable this kind of thing would be massively appreciated!

Aside 1: Obeying equations versus modelling equations

Lying just beneath the surface here is a somewhat intriguing thread to examine, which I’ll do so briefly. There’s a subtle distinction between the equations a system obeys at a fundamental level, and the equations a system can be made to model. In the quantum mechanical case, the quantum processes are described by the Schrodinger equation as their ‘master’ equation. But we can configure reality so that we can make that system imitate the matrices described above. Similarly, whatever equations are governing our biological system (presumably, ultimately, the Schrodinger equation), some arrangement of that system can be made to implement Bayesian inference. I think the authors of the Morphogenesis as Bayesian Inference paper implicitly say something like this, for example here:

To describe the dynamics of an ensemble of information processing agents (as in cells, for example) as a process of Bayesian belief updating, we need to relate the stochastic differential equations governing Newtonian motion and biochemical activity to the probabilistic quantities above. This is fairly straightforward to do, if we associate biophysical states with the parameters of a probability density – and ensure their dynamics perform a gradient flow on a quantity called variational free energy. Variational free energy is a quantity in Bayesian statistics that, when minimized, ensures the parameterized density converges to the posterior belief

You didn’t think I would write a blog post without mentioning the Free Energy Principle somewhere, did you?

Aside 2: The space of possibilities within biology

We asked at the start of this section what the space of biological organisms looks like, and what it contains. I can’t resist mentioning that this space isn’t static, and with synthetic biology we can actually increase the dimensions of the space. For example, the ‘space’ of all possible DNA sequences has as a fundamental constraint that those sequences must be made up of only four different nucleotides (ACTG). But there are efforts to introduce novel nucleotides into organisms, which would enable us to create protein sequences currently unreachable in our ‘little’ ACTG-world! Oh, also, some people recently effectively doubled the size of this space.

As we already mentioned, the ‘space’ of possible organisms has so far been explored by evolution, and we have a gorgeous, mesmerising variety of molecular machines and creature morphologies because of it. We should explore more of this possibility space - we should find out if we can find molecular machines that target viruses specifically (naming all of them after Harry Potter characters, obviously!), we should find organisms that solve our problems with microplastics, and bacteria that devour oil-spills. It’s time to build … a scalable pipeline for designing reconfigurable organisms!

Aside 3: Universal computation in biology

An interesting side-note that complements our discussion above about universal computers: there’s some debate about which systems in biology are actually Turing-complete. The thinking had been that gene-regulatory networks or cellular signalling cascades could be good candidates because they can be modelled as dynamical systems (i.e. systems of differential equations), and there were some proofs that some systems of differential equations can simulate our Universal Turing Machine. But it turns out that the kinds of differential equations that can simulate Turing Machines suffer from a kind of ‘instability’ that renders them quite possibly unrealisable in physical systems. One interesting proposal uses Lambda calculus and RNA to to construct a hypothetical biologically-plausible universal computer.

It’s interesting to speculate on how this meshes with the ‘RNA-world’ hypothesis that attempts to account for the origin of life.

Physical neural networks and The Manifold Hypothesis

Whew, that was a lot of biology. Let’s take a break by considering for a moment the effectiveness of deep neural networks and the ways in which physical systems can implement them.

Why Does Deep Learning Work?

So asks Lin, Tegmark, and Rolnick in Why does deep and cheap learning work so well?. The point they make is that the effectiveness of deep neural nets, which is often ascribed to their ability to approximate any arbitrary function, may be due also in part to physics. Given that “.. the set of possible functions is exponentially larger than the set of practically possible networks”, and that there are something like $256^{1 000 000}$ possible 1-megapixel images (for comparison, there are ‘only’ $10^{78}$ atoms in the universe), how come neural networks so reliably find functions which do indeed find the tiny fraction of these images which represent cats?

Their answer revolves around the same few principles that seem to make physics ‘simple’ (in terms of having relatively few parameters) - symmetry, locality, low-polynomial order. The laws of physics prune down that giant set of $256^{1000000}$ images into a small subset that are actually physical - or likely to be so. They also show various efficiency gains over ‘shallow’ networks that come about because the processes that ‘generate’ natural data tend to be hierarchical.

So this section is less about programming matter and more about asking why a particular type of programming (the optimisation of these deep nets) works so well. But can we connect this all up to actually program matter?

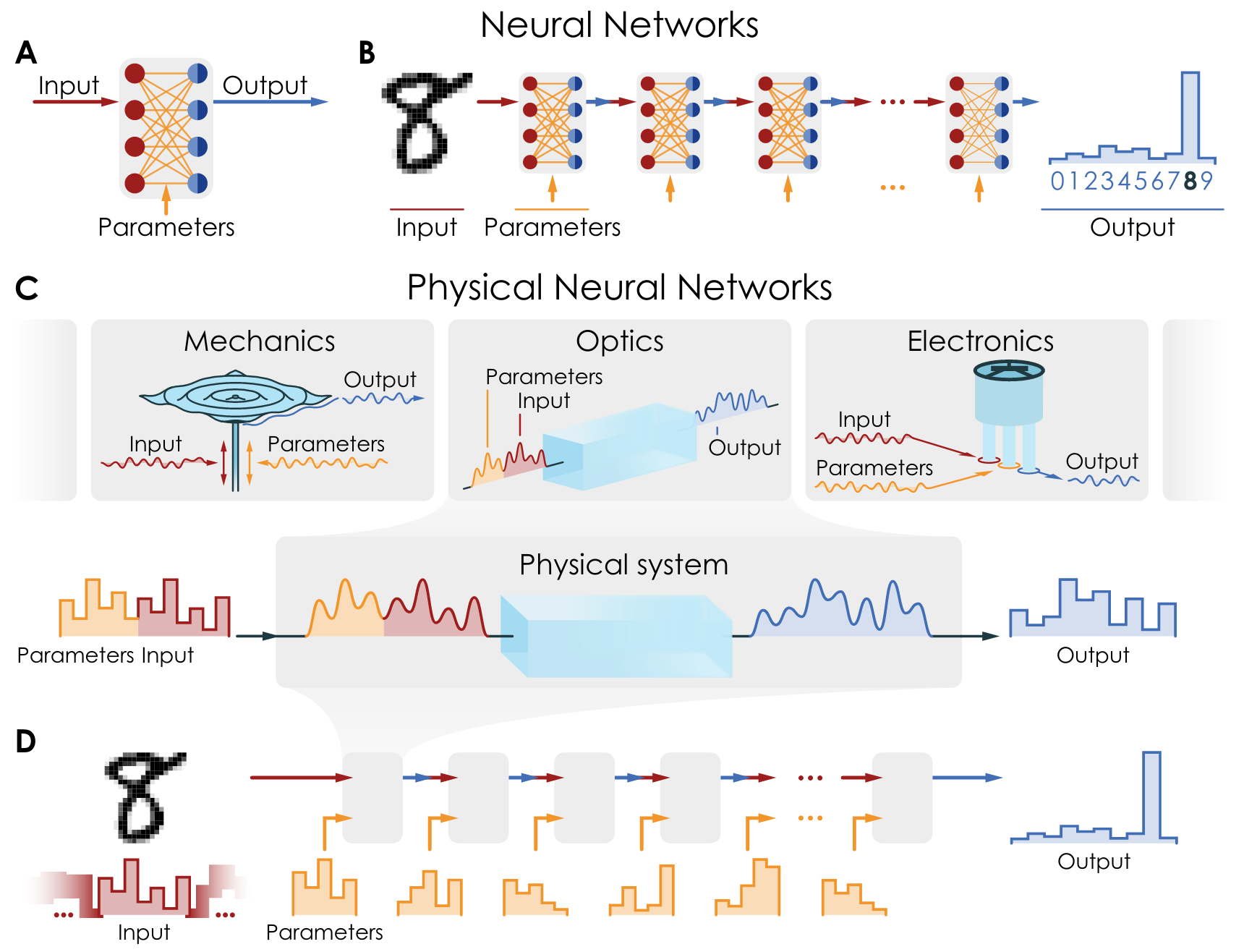

Physical neural networks

This is one implication of the ideas in Deep physical neural networks enabled by a backpropagation algorithm for arbitrary physical systems.

From Deep physical neural networks enabled by a backpropagation algorithm for arbitrary physical systems

The basic idea is that we can ‘encode’ some input into a physical system, like a metal sheet, as a set of vibrations. We can also encode the parameters of our neural net as another set of vibrations which can constructively or destructively interfere with our input vibrations. We can then ‘read’ the output of the ‘network’ as e.g. the wavepattern of vibrations attained after the two sets of vibrations have intermingled. The network is trained by comparing the output of the real system to that predicted by a physics simulator for the system, and then the ‘parameter’ vibrations are adjusted accordingly until the desired output of vibrations is created.

Personally, I find this (and other approaches to using nature to instantiate neural nets) a very satisfying way to ‘programme’ matter!

Drexlerian Nanotech and Von Neumann’s Universal Constructor

We had our first glance at programmable molecular machines in the ‘biology’ section of this post. And as the saying goes “anything worth doing with with Van Der Waal’s forces in organic chemistry is worth recapitulating in a diamondoid substance with covalent bonds”. Well, I’m not sure if that’s how it goes, but I could imagine J Storrs Hall’s birthday cards say something like that.

The goal of nanotechnology - the kind envisioned by Feynman in 1959 and theoretically developed by Eric Drexler in the late 20th century - is to have atomically precise control of matter. So precise in-fact, that we would be able to speak of a new phase of matter - the machine phase:

..it would be a natural goal to be able to put every atom in a selected place (where it would serve as part of some active or structural component) with no extra molecules on the loose to jam the works. Such a system would not be a liquid or gas, as no molecules would move randomly, nor would it be a solid, in which molecules are fixed in place. Instead this new machine-phase matter would exhibit the molecular movement seen today only in liquids and gases as well as the mechanical strength typically associated with solids. Its volume would be filled with active machinery.

The capabilities of truly mature nanotech are astounding. In my favourite book of 2020, Where is My Flying Car?, the author estimates that we could recreate, from scratch “every single building, factory, highway, railroad, bridge, airplane, train, automobile, truck, and ship” in the entire United States …in a single week!. That’s the sheer power and capacity of systems whose native operating frequency is about a million Hertz!

Capabilities of mature nanotechnology

Actually, since the figures truly are astounding, I’ll rattle some off. I’m getting these from pages 428-432 of Drexler’s Nanosystems - Molecular Machinery, Manufacturing, and Computation:

- Atomic precision - construct objects with features of ~0.3 nanometres in length, or 100 million distinct atomic features in a volume of 100 cubic-nanometres

- Diamond-stiffness and strength (~55 times the tensile strength to density ratio of steel)

- Directly convert between electric and mechanical power (and vice-versa) at a power density of ~$10^{15}\ \text{W}/\text{m}^3$, and between mechanical and chemical energy at a power density of ~$2 \times10^9\ \text{W}/\text{m}^3$

- This is enough power density to put a 1000-horsepower engine inside a 1 millimeter cube

- Use the ability to directly thermalise chemical potential energy to store ~$4\times10^7\ \text{J}/\text{kg}$

- Design computational systems with CPU speeds of ~$10^9$ instructions per second, storing ~$10^{25}\ \text{bits}/\text{m}^3$

Nanotechnology and Universal Constructors

John von Neumann pre-empted the discovery of DNA by asking himself how self-replication was possible and consistent with the laws of physics. He realised (I’m paraphrasing David Deutsch from here) that you needed to specify instructions for assembling the system - that you couldn’t simply “copy-paste” the whole thing. From there, and knowing what we do about the universality of another machine that follows instructions on a tape (the Turing Machine), it’s natural to ask whether a universal constructor exists. Is there an arrangement of atoms such that that arrangement can reproduce all other arrangements?

Surely the ability to rearrange matter at will would constitute ‘programmable’ matter in the sense we’ve been investigating here?

Of course, now I should say something about the ‘programmable’ part.

Programming with atoms

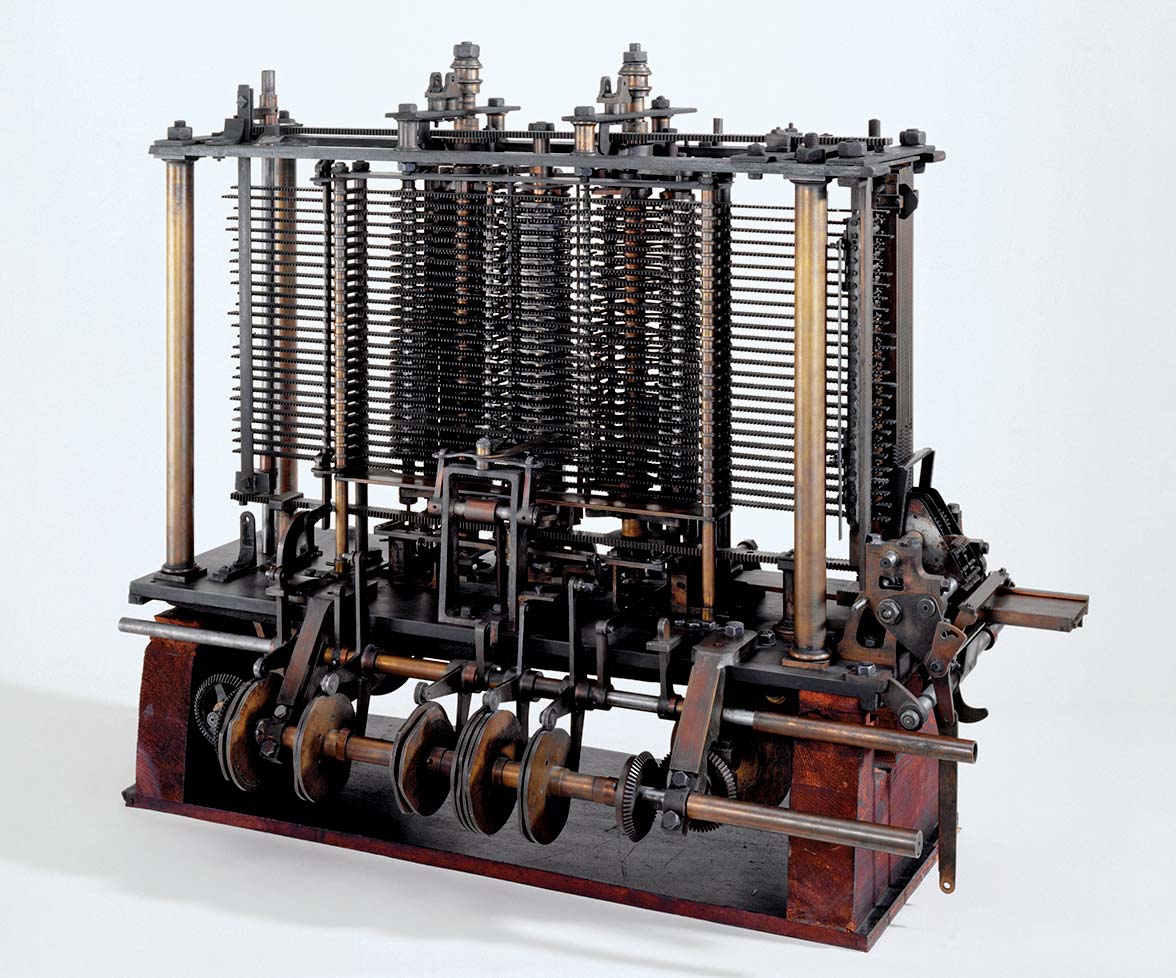

You saw the title of Drexler’s book earlier, right? Nanosystems - Molecular Machinery, Manufacturing, and Computation. In it, Drexler sketches plans for building nanomechanical computers (as opposed to the familiar electronic computers we use for most things). Nanomechanical computers don’t use changing voltages in semi-conductors to represent zeros and ones, but instead represent them using the displacement of tiny rods into specific locations.

Visualise Babbage & Lovelace's mechanical computer, just a few billion times smaller

So if we could build and control systems in the machine phase we’d have a crazy amount of power over physical matter. We’d be able to separate, store, and control vast swathes of the material world! What could go wrong!

Exotic phases and weird physics

Now let’s land this blog post in style!

It-from-Bit

“… every it - every particle, every field of force, even the spacetime continuum itself - derives its function, its meaning, its very existence entirely - even if in some contexts indirectly - from the apparatus-elicited answers to yes or no questions, binary choices, bits.”

So says John Wheeler in Information, Physics, Quantum: The Search for Links, wherein he famously coins the term “It-from-Bit”. Wheeler was looking around at a few astounding facts about the universe and asking if these were hints that information itself may play a fundamental role in our universe.

Landauer and Limits

One of those facts is the link between even the simplest ‘computation’ - erasing a single ‘bit’ of information - and a completely unavoidable expenditure of energy required to do so. This is the famous Landauer limit: the minimum amount of energy $\text{E}$ it’s possible to use to perform the operation of erasing a bit (at a given temperature). The formula is pleasingly simple $\text{E} = \text{k}_\text{B}\text{T}\ln2$ and at room temperature that’s $0.0175\ \text{eV}$ (our computers are several orders of magnitude more inefficient than this).

So computing gets pretty intimately tied to thermodynamics and entropy production - see The physical nature of information by Landauer for more.

Bekenstein and Black Holes

What else? Well there’s a finite amount of information we can pack into a given region of space! And conveniently enough, if you try to pack more information into that space (e.g. adding more bits of computer memory), you can show the whole thing would collapse into a black hole. This upper limit on the amount of information that can be packed into a given region is the Bekenstein Bound.

Staying with Bekenstein for a bit, in an article in the Scientific American titled Information in the Holographic Universe he noted that “Thermodynamic entropy and Shannon entropy are conceptually equivalent: the number of arrangements that are counted by Boltzmann entropy reflects the amount of Shannon information one would need to implement any particular arrangement”. It’s not about exactly the same thing, but I love this Eliezer Yudkowsky post which also points at the connection between knowledge of a system and ability to extract work from it.

There’s a further wrinkle involving Bekenstein here. He noted that if black holes are maximum-entropy objects (in-line with what we said above about not being able to squeeze more information into a region), then the entropy of the black hole scales with the area of the black hole’s event horizon. Insights like this gave us the so-called Holographic Principle, which says roughly5 “that the entropy of ordinary mass (not just black holes) is also proportional to surface area and not volume; that volume itself is illusory and the universe is really a hologram which is isomorphic to the information “inscribed” on the surface of its boundary”.

Qubits and dammit no-one’s name starts with a ‘Q’

One of my 2020 Lockdown pasttimes was watching Leonard Susskind’s ‘Theoretical Minimum’ lecture series. At one point, Susskind is speaking about the logic of quantum mechanics, and the ways in which it is different from classical logic. He then makes a throwaway comment about a deep connection between the number of parameters in the qubit state space and the three dimensions of ordinary space. Not exactly ‘programming’ matter, but aesthetically I appreciate that the fundamental physics of two-state quantum systems just might link up in unexpected ways with the 3D world of everyday experience.

Topological matter

“Hey what’s your favourite programming language? C or Python?”

“Na dude, I only programme in the topological inequivalences of braided anyons”

We’re all familiar with the garden-variety of weird quantum phenomena - the double slit experiment, Schrodinger’s cat, etc. But beyond the garden wall there’s a veritable zoo of bizarre things. Wtf is a fraction of an elementary charge? What part of ‘elementary’ was I misunderstanding? What do you mean those made up mathematical ‘potential’ fields have physical consequences that are more fundamental than the good old electric and magnetic fields?

So here’s another thing: we can alter the properties of matter by creating knots in the hypothetical world-lines that they trace out in spacetime. What? I mean seriously, the idea is that in some dimensions, the topology (the properties of a shape that are preserved if we’re only allowed to smoothly deform it, without tearing or cutting) of some paths through spacetime has a measurable effect on the matter tracing out that trajectory.

I don’t know what things we might programme in this weird topological language. In a pleasingly-Ouroboros-like way, the most frequently given example for what topological matter enables is fault-tolerant quantum computers.

I say let’s programme matter with topology and then use that topologically-protected quantum state to programme everything else!

So is everything just information?

To round this off, Scott Aaronson has a great post on the extent to which information is physical. I recommend it in its entirety if you’ve enjoyed my minor foray into the topic. Here’s Aaronson on the fundamental importance of information in thinking about the double-slit experiment:

We get closer to the meat of the slogan [“Information Is Physical”] if we consider some actual physical phenomena, say in quantum mechanics. The double-slit experiment will do fine.

Recall: you shoot photons, one by one, at a screen with two slits, then examine the probability distribution over where the photons end up on a second screen. You ask: does that distribution contain alternating “light” and “dark” regions, the signature of interference between positive and negative amplitudes? And the answer, predicted by the math and confirmed by experiment, is: yes, but only if the information about which slit the photon went through failed to get recorded anywhere else in the universe, other than the photon location itself.

And so, even if we reject ‘It-From-Bit’, we must still account for ‘information’ - the very stuff manipulated by any program - in our most basic physical theories.

Conclusion

I hope you enjoyed this tour of the ways matter can be programmed, as well as the many digressions to speak about computing in general. For more in this vein, I highly recommend Michael Nielsen’s ongoing exploration of the future of matter.

Comments, twitter DMs, and links to more interesting stuff are always appreciated!

Also, I am working on part 2 of the FEP series, I promise!

-

More technically, an approximation, but it doesn’t really matter ↩

-

I don’t have space or scope here to explain why we’re using vectors, or what all the symbols are. I know this is kind of unfair. But my argument in the rest of this post doesn’t depend on the maths specifically, it’s the general idea of representing pieces of math in physical systems that we care about. Also, another plug here for quantum.country - if you want to understand all the notation, they explain everything far better than I can! ↩

-

If it sounds like he’s hedging a bit, he is, and the full interview explains the technicalities as to why, but as far as I can tell, he still believes that a quantum computer could simulate any finite physical process. ↩

-

Actually, if we take seriously that biology and neural nets are similar, in that they were both created by very powerful optimisers (evolution and stochastic gradient descent, respectively) working on highly redundant systems, maybe there is an extension of this analogy that bridges our current approach of understanding biology to the approaches we use to understand the internals of deep neural networks? Interpretable deep learning has been a possible attack vector for understanding the brain for a while (see e.g. here: https://distill.pub/2021/multimodal-neurons/), but maybe there are wider applications? See https://distill.pub/2018/building-blocks/ for more on interpretability. ↩

-

I’ll just quote Wikipedia directly here, presumably to frustrate my primary school teacher, who said never to do this ↩