Hamming-Enablers and The Tech In Techno-Optimism - part 1

Part 1 - Computation, Intelligence and Coordination + Progress, Institutions, and Politics

- Hamming Enablers

- Computation, Intelligence, and Coordination

- Progress, Institutions, and Politics

- Conclusion

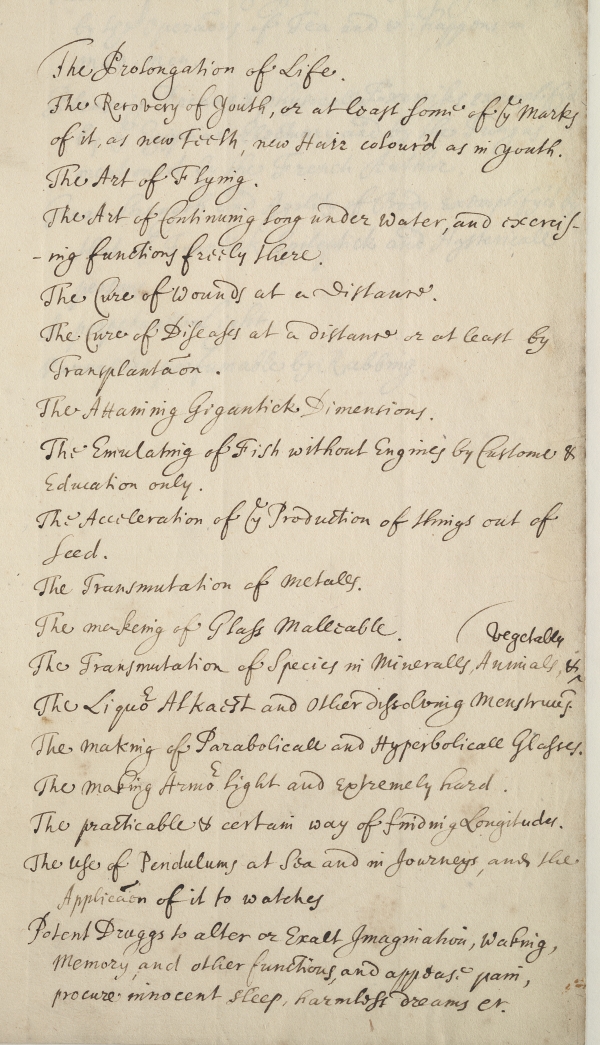

Robert Boyle (yes the one from high-school chemistry) kept a list of technologies he thought humanity should pursue:

The list is surprisingly prescient, hinting at flying machines, submarines, life-extension, and psychedelics.

I too have a list (but alas, no highschoolers have heard of Tumiel’s Law) and this post is about that (the list, not the law). But first we have to talk about Hamming Enablers.

Hamming Enablers

Boyle penned his list in the 1600s, which means that 300 years ago it was possible for a smart natural philosopher to conceive of these things being possible. So why the ~250 year delay between the list and the Wright Brothers? Why are psychedelics only really entering the (clinical) mainstream today? Why is human longevity not a solved problem already?

Each technology will have its own story of economic, scientific, design, and production challenges, but the general point I want to get at is the gap between technologies we can easily imagine (or suspect are possible), yet don’t currently know how to tackle.

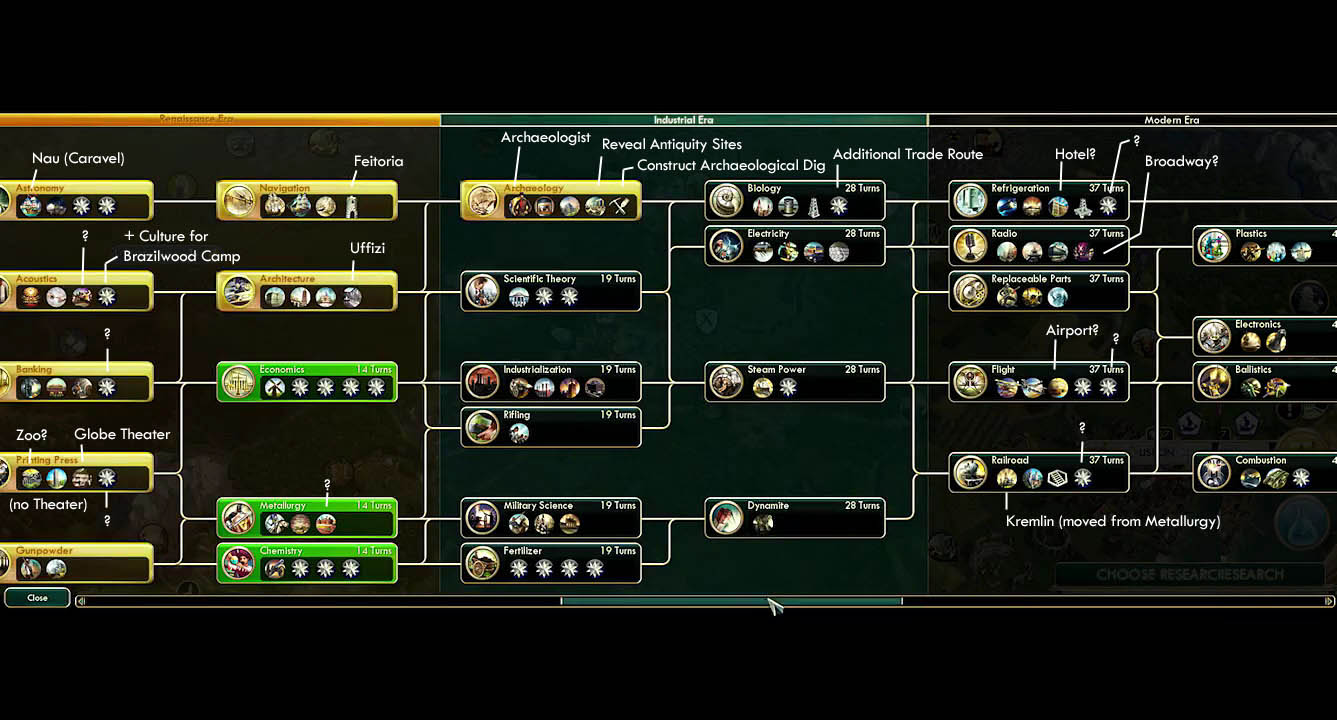

The easiest way to understand this is through the idea of a tech-tree in video games: you can’t just unlock nuclear power if you haven’t first researched mining, uranium refinement, the physics of nuclear chain reactions, etc. It’s easy for anyone to look at birds flying and know that in-principle, heavier-than-air-flight is possible. It’s more difficult to backchain to what intermediate developments in fluid mechanics, calculus, materials science, and powertrain development are needed to build an aeroplane.

So what’s a Hamming Enabler? Richard Hamming (of Bell Labs fame) in his famous speech You and Your Research has this to say:

Most great scientists know many important problems. They have something between 10 and 20 important problems for which they are looking for an attack. And when they see a new idea come up, one hears them say “Well that bears on this problem.’’ They drop all the other things and get after it.

Gian-Carlo Rota, in his advice to his younger colleagues, quotes Richard Feynman, who offers a similar piece of advice:

Richard Feynman was fond of giving the following advice on how to be a genius. You have to keep a dozen of your favourite problems constantly present in your mind, although by and large they will lay in a dormant state. Every time you hear or read a new trick or a new result, test it against each of your twelve problems to see whether it helps. Every once in a while there will be a hit, and people will say, “How did he do it? He must be a genius!”

And it’s not just dudes from the 1900s who think this is something worth doing! Here’s Ed Boyden1 saying much the same thing:

… I really try to make my schedule safe for serendipity. I spend a lot of time going over old conversation summaries. A lot of the old ones are about ideas that ended in failure, the project didn’t work. But hey, you know what? That was five years ago, and now computers are faster, or some new information has come along, the world is different. So we’re able to reboot the project

So we have two rather-famous-Richards and neuroscience superstar Ed Boyden giving similar advice: know the ins and outs of a few particular problems, the current bottlenecks and limitations. Then as you bump into novel ideas, analytical techniques, manufacturing, or technical procedures, you can quickly ask yourself if the new thing could possibly enable progress on one of your pet problems. I call a new process, material, technique, model, mathematical paradigm, or physical law which enables progress on a difficult technical problem a Hamming Enabler.

Hamming Enablers are interesting retrospectively and prospectively. Retrospectively, we can ask why powered flight was not invented in the 1600s, or we can ask what had changed around 1903 that suddenly made it tractable. Prospectively, we can ask what tech a given new development might Hamming-Enable (does that make sense?), or reverse the question and ask what Hamming Enablers we might require to reach a certain technological goal (the backward-chaining idea I mentioned earlier).

So, without further delay, let’s step through the list2

Computation, Intelligence, and Coordination

Heterogenous Compute, and Non-Von-Neumann architectures

Moore’s Law is slowing down, and every year chip-makers are doing their best to squeeze more performance out of semiconductor design. To the extent that they fail or fundamental physical limitations in the size of semiconductors set in, we’ll need to use other strategies to see continued progress in computing power.

The Apple M1 chip is a good example here: the M1 is what’s known as a System on a Chip (SoC). Instead of each component in the computer plugging into a motherboard, the whole thing is on one piece of silicon, minimising distance between components and allowing for optimisation of the unit as a whole.

At the extreme end of hardware specialisation we get Application Specific Integrated Circuits (ASICs). Here, we just hardcode the program we want to execute into the logic gates of the processor, sacrificing the flexibility of more general architectures for pure speed.

Heterogenous compute captures the idea of combining ASICs into our devices (laptops, smartphones, self-driving cars, etc.) for some of the most common tasks, thus getting the speed and efficiency benefits of an ASIC while preserving the generality of the device. For example, the iPhone has a dedicated image-processing chip alongside its general processor, and we can imagine generalising this for almost any device that finds itself performing one or two computations far more often than any others.

An obvious area we’ll see something like this in is in AI-specific hardware. TPUs (tensor processing units) are already one attempt at this, but we can do better. If we think of computing as a process happening in a specific medium, with a specific architecture, then we can ask if there are other computational mediums, and other computational architectures that might be useful. Right now, the medium we use to compute is electronic - electrons in moving in transistors, and the architecture is essentially3 the Von Neumann Architecture.

Beyond Electronic Compute

Moving electrons around has its limits. There’s resistance and heat dissipation to think about, as well as their mass and the amount of energy needed to move them at a given speed. Photons on the other hand… also have a bunch of problems as a computational medium (hence requiring progress in materials science), but they don’t have mass, so that’s a start!

Nonetheless, some concrete progress has been made, especially if (in keeping with the heterogenous compute theme above) you restrict the types of operations you want to perform. Modern deep learning requires a lot of matrix multiplication, and it seems like there’s been relatively more success using light to compute in this setting:

- Researchers have shown dramatic efficiency improvements in training neural networks using photons.

- A startup called LightOn AI has developed an entire photonic processor. This is cool because they used this processor to implement a non-standard algorithm for training neural nets called Direct Feedback Alignment, which touches another theme from later in the post. I’ll have more to say about going ‘beyond backprop’ in the AI section of the list, but noting how items on this list are synergistic and Hamming-Enable each other is like half the reason I’m so excited.

Beyond Von Neumann Compute

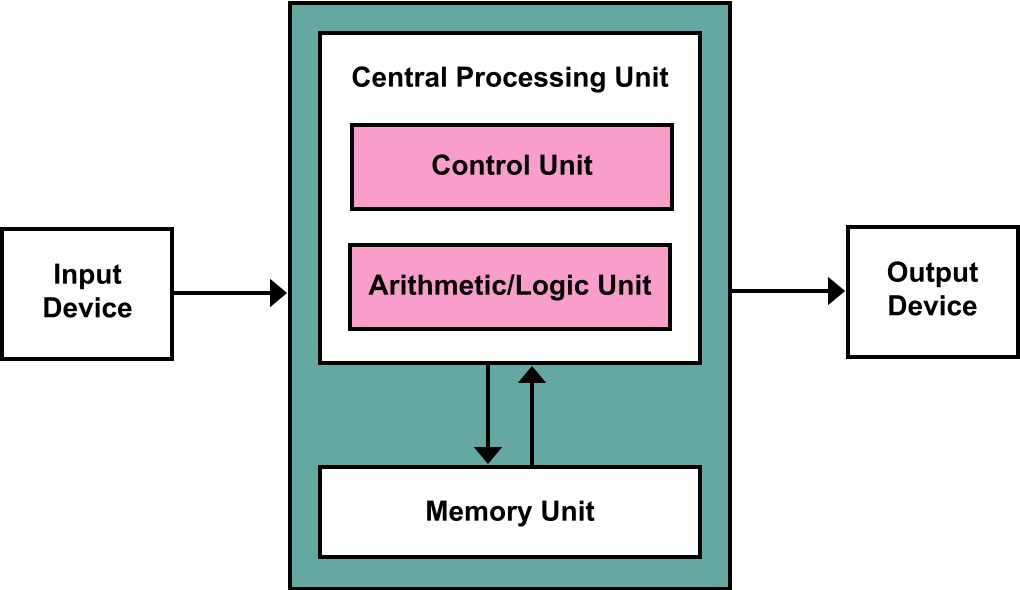

Our abstract model of computation comes from the Turing Machine. But we want a concrete implementation if we’re to do any actual computing (ain’t nobody got time for an infinitely long tape). John von Neumann gave us his eponymous architecture, and it’s pretty recognisable in just about any computing-device you’re likely to have. It consists of inputs (touchscreen, mouse, keyboard), a CPU which executes the instructions made by programs, external memory, which stores data and programs, and some outputs (screen, printer). Note that the CPU and memory are separated, meaning data needs to be transferred between the two. The von Neumann bottleneck refers to the limitation imposed on the speed of computing because of the latency introduced by this data transfer. What’s worse is that while we’ve both sped up our CPUs and increased the density and capacity of our memory, the rate of data transfer has remained relatively stagnant, meaning the von Neumann bottleneck has gotten worse. We get around it with a bunch of tricks like RAM, caches, and multithreading, but as a limitation its baked into the way we build computers.

So what if we just didn’t do that? These are the so-called non-von Neumann architectures, and at their most basic they try to find a way to do ‘in-memory’ computing, so that the CPU doesn’t have to wait around for data to be shipped-in from memory. A subset of these go by the name ‘neuromorphic compute’ because of some (loose) analogies to biological neurons. This is also a form of heterogenous compute, and one of the main reasons to make a neuromorphic computer is to allow for more efficient use of artificial neural networks, which is a nice synergy to have if AI is going to be increasingly important!

AI

Having a section like ‘AI’ in a list of things to be optimistic about is too broad, and not exactly a revelation to anyone likely to be reading this. Like all of the things on this list, the people working in this field tend to role their eyes at lists like these because they actually know enough about the day-to-day challenges of the work to know that something simple sounding like “use AlphaFold to enable the next generation of drug discovery” is sweeping a lot of practical tedium under the rug. This is probably true for everything on this list, so we might as well acknowledge it here.

So what, specifically is happening in AI right now that should give us optimism?

One is just a personal hunch, and that is that there really is progress in the field. I don’t have a legible description here, but AI right now feels alive and generative in a way which few fields do. Another personal hunch is that there are many specific techniques which are aimed at solving individual problems getting pushed to Arxiv daily, and no one has the time to pick the low-hanging fruit of combining them. By this I mean that for many of the specific problems someone could point to with AI, someone is publishing something to the Arxiv that addresses it. It might not solve it completely, or it comes with tradeoffs, but the turn-around times are impressive.

For example, let’s use the relative inefficiency and large computational overhead of using Transformers in all the super powerful GPT-X-esque language models. Models like these come under fire by AI critics, who cite the cost and environmental impact of using all those GPUs, or the amount of data needed to train the model, as problems. But then, in the span of just 6 months (from January to June of 2020) there were several different proposals addressing both these issues, including the Reformer, the Performer, the Linformer and others with less catchy names.

On one hand. I can imagine a sceptic saying something like “those are just incremental improvements pushed out to get citations”, but a) it’s absolutely awesome that the field moves fast enough that multiple serious solutions are posted so quickly to serious challenges, and b) the incentives of academia are not set up for researchers to refine those techniques and set them up for production-level AI, let alone combine disparate improvements across research labs and productionise the combination, making them seem more incremental than they really are. The times where this has happened (e.g. the pretty standard combination of ResNets + dropout + SGD + batchnorm for many computer vision tasks) has produced phenomenal results, and importantly, each of those techniques seems to work synergistically with the others. My gut feeling is that there are other unexplored, unrefined (to production-level, not academic research level) combinations just waiting to be plucked from the Arxiv!

Okay, enough “gut feelings” and “hunches”, let’s be concrete!

First, my one paragraph summary of how I see the state of AI right now:

Humans have “solved” many of the original challenges of the field (image recognition, text generation, game-playing), mostly using classique supervised deep learning. Big efforts will be made to continue adding parameters to Transformers to see when, if ever, this stops improving their performance. Current success is largely due to some brilliant architectural and training tricks, all mashed together with oodles of labelled data from the internet and lots of computing power. Transfer learning makes these pretrained models available to anyone and so now anyone can benefit from that one time outlay of compute to build more specialised models. Reinforcement learning remains more challenging, but things like MuZero look seriously promising.

So what’s new:

Well self-supervised learning seems to be going through a bit of a renaissance. A big sticking point in AI right now is the availability of labelled data from which to learn, and the ability to do common sense reasoning even on situations you haven’t specifically trained on. Self-supervised learning tries to address the former by learning something about the (statistical) structure of the data in general, and in doing so, possibly improve at the latter. A few new approaches have surfaced recently, often using the idea of “contrastive learning” to setup the agent to try and predict unseen parts of the data, given the context of seen parts - no labels required! I think some scheme like this is one way we could build robust world models for our model-based RL agents, and I think good world models are the key to some of the “common-sense” reasoning some people bemoan AI for lacking.

Another thing I’m optimistic about is AI augmenting and enabling new physical possibilities. It seems many people currently think of ‘AI’ as either the thing that makes your Instagram feed eerily mirror your innermost thoughts, or something to do with making robot dogs walk around. Instead, what we should focus on is that we have a decade of experience training optimisers that are extremely good at traversing high-dimensional spaces, and now we get to choose whether that space is about which ad to serve you on YouTube, or about the tiny proportion of physical arrangements of molecules that generate a particular response in a petri-dish of cells.

AI for scientific discovery is an obvious Hamming Enabler. Right now, a group of researchers can discover new facts about physical materials just by exploring the latent space of a language model trained on the materials science literature. More generally, we can think of doing reinforcement learning in unique state-action spaces4. So instead of imagining an agent being able to choose how to move through a physical environment using familiar actions to those available to us as humans, we could imagine our state space as being the molecules present in a beaker, and which are bound to which and in what positions. The action space could be the set of known chemical reactions, or application of some catalyst, and the agent could have the objective of creating a molecule we specify before-hand, but don’t currently know how to synthesise.

Generative design also seems relevant to point out here. It’s a neat bonus of most models that once you’ve trained them to (e.g. in the case of AlphaFold) predict protein structure from the amino-acid sequence, you can probably invert them and do the reverse, or you can use the latent space that encodes all the knowledge to ask further hypothetical questions about protein structure. A lot was made about drug-discovery using AlphaFold, but I tend to think of it as the first steps towards AutoCAD for molecular machines (and believe me, proteins aren’t just ‘like’ molecular machines. Proteins are molecular *machines! [paywalled]). So predicting proteins accurately is certainly impressive and useful, but my guess is that there’s far more value to be extracted by some combination of an RL agent able to act with something like AlphaFold as its world-model. That being said, the state of AI+protein design is stupendously exciting - just look at Einstein.ai’s use of language models for protein design!

More than this, I think the people trying to do something different from just scaling up Transformers have a chance of making a breakthrough. Self-supervised learning is part of this, but some even more fundamental shifts are afoot. I continue to think that Karl Friston’s Active Inference, and the related Free Energy Principle, will have important things to contribute to mainstream AI. Early signs of this are:

- Active inference based models outperforming traditional ones in the non-stationary multi-armed bandit task (paper).

- Active inference encompassing and extending traditional reinforcement learning (paper)

- Active inference ideas making their way into publications by big, industry facing research labs like DeepMind (paper)

- Predictive coding (key neuroscientific account of brain function, heavily studied by FEP/active inference crowd because of formal similarities) shown to approximate the backpropagation algorithm (key ingredient in training our current deep neural nets) (paper)

More things to be excited about:

- I remain excited about neural net architectures that take advantage of the structure or symmetry of the data - gauge-equivariant neural nets, graph neural nets, geometric deep learning - all seem full of possibility

- Architecture search as well as learning to create optimisers which learn to train themselves point to a path where “end-to-end” ML means also learning an architecture and an optimiser that’s particularly suited to your task. Related: the lottery ticket hypothesis and possibly using this to enable much smaller edge networks

- Physical neural networks. Heavily related to heterogenous compute above, but there’s even more awesome stuff in the mix which I think has barely been explored. I have an entire blog post in the works about these!

- Neural cellular automata. The extensions already created to this idea are crazy. See: Towards Self Organised Control and Growing 3D Artefacts and Functional Machines with Neural Cellular Automata. As a heuristic model of complex system development, and a way of creating robust self-organising systems, I think this is a promising direction of research.

Crypto

and thus the transformation into tech-bro was complete

Crypto gets a bad rap. For many it’s the perfect combination of the vitriol and tribalism of the internet, muddled up with the embarrassment, fear, and greed of personal finances. But there are some specifics about crypto that excite me, especially if we think of it as a general Hamming Enabler for a host of heretofore untried experiments in social coordination, cooperation, fundraising, and governance.

As a warm up to the possibilities, let’s contemplate this tweet:

I think this matters because of 2 things: 1) permissionless innovation, and 2) fast feedback loops (bonus for the feedback in crypto usually being monetary, so the incentives are pretty real from the get-go).

Arguably one of the big reasons we had such big slowdowns in innovation post-1970 is that we regulated away our ability to innovate. If you need millions of dollars in lobbyists, and years of filing paperwork to get your HyperLoop installed, it’s probably going to be really hard to iterate fast enough to make mistakes and learn from them, and you wouldn’t want to because delays and redesigns will be costly and subject to more paperwork5. Compare that to the relatively unregulated software sector from 2000-2016, where (even if bad things have happened), it’s hard to deny that e.g. the ideas and implementation of companies like Uber and AirBnb are innovative approaches to solving their respective problems.

Crypto, if nothing else, has opened up another frontier for people to play around and try out new ideas. Specific coins may come and go, and scams will be inevitable (sort of like the early internet), but at the same time a core of dedicated, super-smart people with genuine morals and a desire to create something important will be working away like crazy in the background. Take a look at Numerai for an example of something which I would claim was Hamming-Enabled by the development of cryptocurrency. I also think that we’ll see the DAO concept continue to develop and mature, which might itself Hamming-Enable new ways of funding research and other public goods. Plus, there’s never been a better time to be a mechanism design researcher, because suddenly you can try out fancy things like Quadratic Funding, at scale, in the wild, and learn from that.

More things to be excited about:

- Ethereum scaling solutions (optimistic and ZK-rollups) + sharding in the longer term look like they will work, and when they do I think of them as being Hamming Enablers for the entire Ethereum ecosystem

- Lots of individual things in the DeFi space. It’s a bit of a contrived example, but think about flashloans for a second. The fact that suddenly anyone on earth can borrow hundreds of millions of dollars with zero collateral and no need for a credit check is wild. So far it’s mostly been used for arbitrage opportunities (and attacking/exploiting liquidity farms), but as Hamming-enablers go, if we’re just asking the question “what’s something that’s now possible that previously wasn’t?” this is one of those things. I think we’re all just waiting for someone smart to show us some new, powerful application that no-one else has thought of yet.

Progress, Institutions, and Politics

Progress Studies & Techno-Optimism

Yes, I’m optimistic about the optimists

Stagnation - both technological and economic - is bad. Luckily, having identified the shape of the problem (or at least maybe the year it started?), we can start to look for solutions. The “progress studies” crowd6 - a group of people determined to understand the causes of productivity stagnation and how we can return to or even exceed previous high levels of growth - is a great signpost to others that we should-and-do care about pushing society down a path of growth and technological development.

I think there’s a whole conversation to be had about the kinds of memes we distribute and the extent to which our media and our civilisational storytelling can be a driving force for progress. Personally I find reading the techno-optimists to be infectiously optimism-inducing, and I think that’s a flywheel worth spinning up!

PARPA, New Science, Focused Research Organisations, and all that

Is scientific progress slowing down? And if it is, how much of that is due to intrinsic factors (e.g. picking all the low-hanging fruit to be discovered) versus something about the way we do science? I am strongly in favour of diversifying our funding models and talent-selection-institutions, and that’s why I’m excited about proposals like Private DARPA by Benjamin Reinhardt, or Focused Research Organisations by Adam Marblestone and Samuel Rodriques, or Alexey Guzey’s New Science. It’s also why I’m optimistic about crypto because, on the margin, having a different cohort of wealthy people with a higher than average predisposition towards techno-optimism, enabled by new mechanisms like DAOs and various yet-to-be-invented smart contracts, seems like it could enable a bunch of people to contribute towards R&D who otherwise wouldn’t have!

Charter Cities

The basic idea of a charter city is this: a bunch of people approach a nation-state and negotiate some contract to create a special jurisdiction somewhere in their country and build a city. The city builders get to experiment with best-practices in-governance, and can use the blank-slate to try encourage (i.e. set up innovative incentive structures) especially high rates of growth, entrepreneurship, sustainablility, or whatever the founders and the population care about. In exchange, maybe they funnel some percentage of the city’s taxes back to the nation state, leaving everyone better off than if there had been no charter city.

Again, in the spirit of letting a thousand flowers bloom, I think the charter city space is exciting. This follows because, if you think that maybe we’re hindering our ability to build by regulatory-strangulation, having diversity of regulatory environments will allow for more experimentation.

Scott Alexander has been doing a great job of dissecting various attempts at creating charter cities and things like them, and also has a detailed review of the charter city, Próspera.

Mechanism Design & Social Technologies

I think two big Hamming-Enablers for meaningful mechanism design will be the combination of usable augmented/virtual reality devices (think e.g. a pair of glasses that could overlay everything you currently see on your iPhone onto the world in front of you, so no need to look down or stop what you’re doing) and the crypto stuff we’ve talked about earlier. The AR side helps us bring our digital incentive tools out into the physical world. The crypto side is useful for creating ecosystems with financial incentives and rules enforced by code.

I think that coordination problems problems and inadequate equilibria are at the root of much of what’s wrong in the world currently, and that, even though they’re amongst the hardest problems out there, on the margin it’s worth investing in technologies that mitigate them. If we’re going to become a ridiculously powerful civilisation, we’re going to need ways to coordinate and prevent e.g. AI-arms-races, or further nuclear-proliferation, or any race-to-the-bottom where ‘the bottom’ = civilisational destruction.

On a less existentially-critical note, designing better policy and incentive structures is worth thinking about generally. I remain a fan of Glen Weyl’s RadicalxChange project, and his book with Eric Posner was the thing that convinced me that there could be solutions to these sticky coordination problems at all. On a related note, I’ve enjoyed reading Samo Burja’s analysis of the importance of social technology in creating and sustaining successful institutions.

Meaningness, and meta-rationality

This last entry might seem out of place on a list that’s been primarily technology-focused, but if we are to increase our power over the universe, we should invest a commensurate amount of energy in learning to use it wisely. I think the EAs and other longtermists are making a good start here, but something that’s made the most difference personally is David Chapman’s work at Meaningness, Vividness, and on metarationality.

It’s hard to say where to start because his writing is this sprawling nebulous living document, but here, here, and here are pretty solid jumping off points. Chapman gently builds up a framework for dealing with the dimensions of what he calls “meaningness”. The tagline for the site is “Better ways of thinking, feeling, and acting—around problems of meaning and meaninglessness; self and society; ethics, purpose, and value.” and it’s pretty accurate. It’s hard to try and vouch for this particular set of ideas about meaning without sounding like every other religion/cult/self-help-guru trying to advocate for their favourite One True Solution to Your Life’s Problems. Thankfully, Meaningness isn’t meant to be a self-contained personal philosophy that’s fully general. Actually, that’s kind of one of Chapman’s points - that no system can ever be final and all-encompassing. It’s the thing I’ve recommended most often to friends when they’re having problems that can’t be solved with a debugger or a trick for doing a weird integral.

Conclusion

What have I left out here? What else is there to be excited about? Obviously this list is far from exhaustive and is more ‘personal opinion’ than me saying “objectively these things are the best”.

The list continues in part 2, where I talk about everything I’m excited about in Materials, Molecules, and Manufacturing as well as Biology, Medicine, and Biotechnology. If there’s anything you think I should check out in those areas before then, my twitter DMs are open!

-

Ed Boyden’s lab birthed both optogenetics and expansion microscopy, which have both been gigantic Hamming-Enablers in neuroscience research ↩

-

Initially, I wanted to work through the Hamming Enablers for each thing on my list - both in terms of what is now enabling that thing, and what it might be a Hamming Enabler of, but honestly I just don’t know enough about many of the ideas to reliably do that, so instead I’ll leave some of it as an exercise for the reader. I think the list has value in-and-of itself so I’ll include it in its entirety ↩

-

Yes yes, Harvard architecture. But Non-Von Neumann sounds cooler than Non-Harvard ↩

-

In RL, the state space is all the possible states the agent could be in. Typically this would be positions in a gridworld. The action-space is the space of available actions e.g. at every timestep pick one of [walk left, walk forward, walk backward, walk right, stay still]. My argument is that people tend to forget that state/action spaces can be a whole lot more abstract than that, and that enables a lot of exciting applications ↩

-

maybe the thing I admire most about Elon Musk is the fact that he actually tried to innovate in a bunch of these areas that are prototypically stymied under regulatory nonsense (spacetravel, energy, full-self-driving) ↩

-

See for example the excellent https://rootsofprogress.org/ ↩