Your Algorithmic Reflection

Google, Facebook, Twitter, and their advertisers want to shape your behaviour. This doesn't have to be bad.

Most people are aware that algorithms shape their online experience. Some people understand that the algorithms’ underlying incentive is to maximise time spent on-site and number of ad-clicks. Few people know how to use this to their benefit.

The 2016 US election saw the popularisation of the terms “filter bubble” and “fake news”. The first refers to algorithms selectively showing social media content that confirms your existing worldview and systematically excluding all but strawman versions of opposing viewpoints from your feed. The second is a consequence of this: the algorithms will propagate the most polarising, least-nuanced views because these naturally stir reaction and attract clicks. At some point, the view becomes so distorted it’s patently false and yet wildly popular within a filter bubble. I’d flesh this out more, but CGP Grey has a wonderful short video explaining just this, so you should go watch that instead.

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly of your Algorithmic Reflection

Combatting fake news and filter bubbles is vital, but here I want to ask what these algorithms teach us about ourselves and how we can use this knowledge to our advantage.

YouTube, Facebook, and the rest have spent a lot of money developing machine learning systems that will keep you hooked on their platform. They do this by accumulating information about what you seem to like, showing you some suggestions, learning from your reaction, and repeating the process 1. What each company is racing to do is build the most accurate model of you they can because an accurate model of you gives them the power to predict what you might like in the future.

This is my key argument:

- Algorithmic content suggestion is here to stay

- Algorithms try to understand your interests, personality, and identity to better serve you content you will enjoy - thus keeping you on-site longer

- The way the algorithms do this is by observing your current browsing habits (what you do and don’t click on, what you watch and for how long etc.) and the browsing habits of people ‘like you’ (people engaging with similar things and what else they seem interested in) and building a model of you based on this data 2

- In this way, our newsfeeds and suggestions become a reflection of us - our algorithmic reflection

- Therefore, we should act in a way which puts the algorithms to work for us so that what is reflected back to us becomes both aspirational (because it represents us at our best) and self-fulfilling (in that consuming better content will shape us into better people, who thus desire better content).

Contrast this last point with The Unhappy Death-Spiral of social media that plays out as follows:

- Open your platform of choice and scroll. The timeline is infinite, the videos on autoplay

- Halt! The thumbnail has a cat and the all-caps caption ending in “🔥🔥🔥😂😂” has alerted you to the presence of something important. 41K heart reactions can’t be wrong

- Train the algorithms to predict that you value the mundane, the clickbaitey, the controversial-but-lacking-in-nuance

- Receive suggestions which fulfill this prophecy, consume them in turn, reinforce the algorithm’s model of you

- Minutes pass and accumulate into hours. Bleary eyed and invariably feeling just a little worse about yourself, return to what you were meant to be doing. Bonus if you lament to a friend that you “just don’t have time for hiking or coffee or painting like you used to”

This is a pattern I have repeated more times than I’m comfortable admitting. It’s something I see my friends do, and it’s something I’m sure most readers have experienced, especially if you’re young enough not to have known a world without social media.

We’re collectively adrift in an ocean of online content and most of us are caught in the doldrums (the latitudes where sailors would spend months trapped, just waiting for a wind - an apt metaphor for the difficulty of escaping the Unhappy Death Spiral above). We find ourselves in these doldrums, directed there by algorithms tasked only with keeping us in the ocean. It’s here that we see our chance of escape, for the algorithms don’t care where in the ocean you are, just that you remain 3. The doldrums are a popular destination for the algorithms to steer you into because they work on just about anyone. To see this effect in action, just look at the kind of content that YouTube shows a first-time user who’s just signed up:4

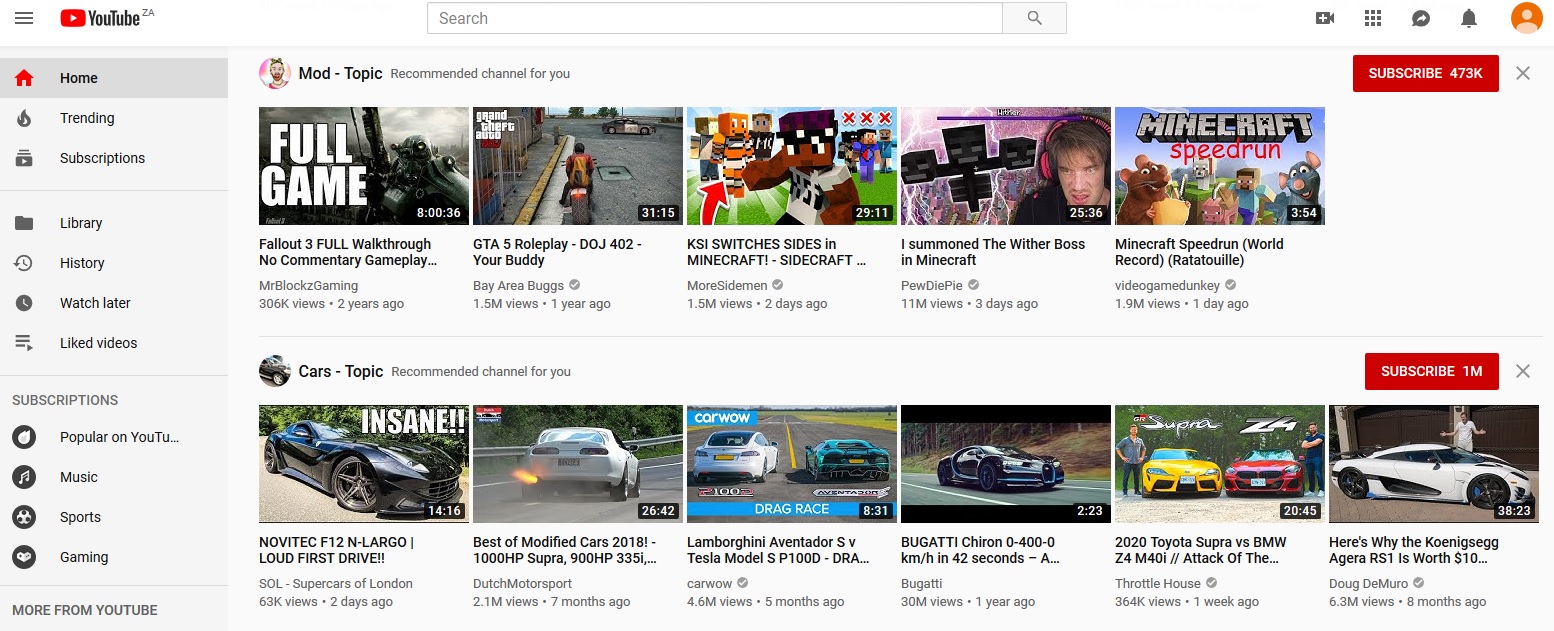

A first look - I think the video game and car suggestions are the algorithms’ best guess for 20-something men?

A first look - I think the video game and car suggestions are the algorithms’ best guess for 20-something men?

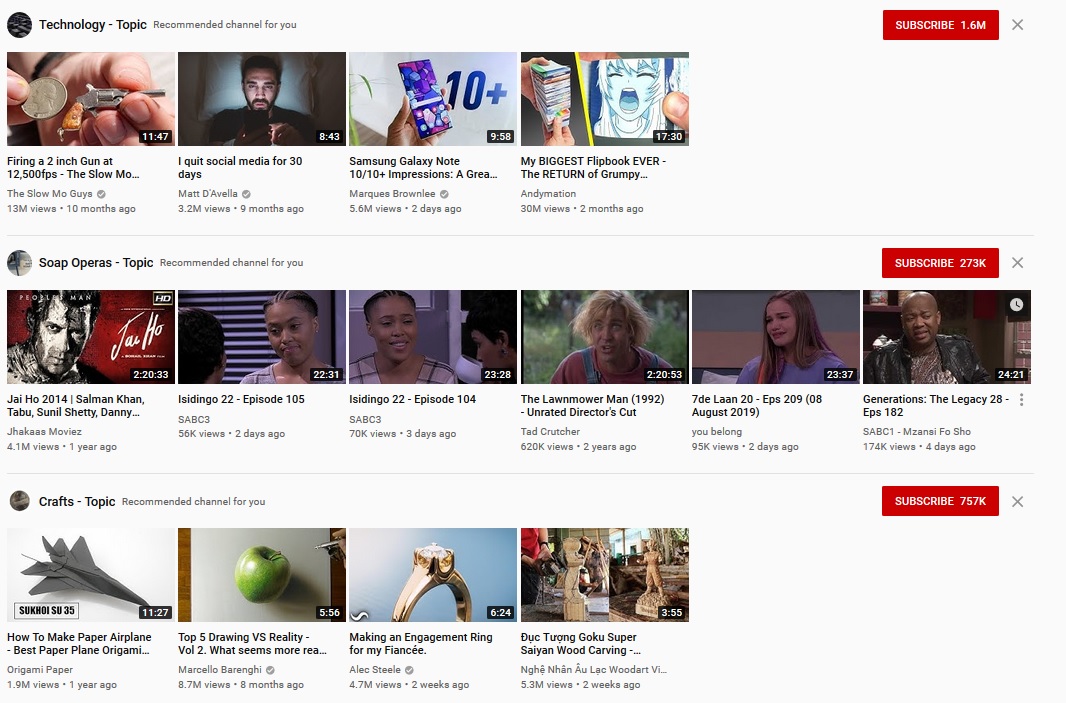

Notice that just based off of my demographics, YouTube’s algorithm has identified some topics and videos they know from experience are likely to get me to stick around. Scrolling down a bit shows these suggestions. You can see my browsing location has made the algorithm select some local Soap Operas for me:

Not exactly Khan Academy, is it

Not exactly Khan Academy, is it

I think the first thing to notice here is just how terrible most of these videos are. Many are clickbaitey; several fall into that strange category of simple things that humans find oddly satisfying, things which abuse some novelty switch deep inside us, like this video of someone testing to see if sharks can detect blood.

I haven’t watched it, so I don’t know what happens. But 31 million people in the past week have. That’s more people than live in all of Australia. That’s so many people that you could have everyone in Australia watch it and share it with everyone in Puerto Rico and everyone in Slovenia and there would still be a million views unaccounted for.

My point here is not to denigrate content creators. If making this kind of YouTube video is what you do, then by all means continue. My point here is to say that for many people, this kind of content - and its analogues on Facebook, Instagram, and the like - is pushed by algorithms because it easily captures our attention without really improving anything else about us. And once we’ve revealed a weakness for this kind of content, we’re bound to be shown more like it, binding us to an algorithmic reflection of ourselves we don’t really like. My point here is that we can do better!

There’s an oft-repeated quote that you are the average of the five people you’re closest to. There’s another that says “you are what you eat”. We’re treated by algorithms as the average of the five-million people closest to our demographic group and we are being force fed their media-diet.

Creating a better reflection - the case for algorithms

Consider for a second the power of these algorithms. They trawl the vast landscape of new content generated every day and manage to reliably identify the few pieces worth seeing. Of the 500 hours of YouTube videos uploaded every minute of every day, or the half a billion tweets sent daily, you see the tiny fraction that are worth it 5. At least in theory they’re worth watching - in practice they’re often just the most polarising, overstated, and clickbaitey.

Remember though, all the algorithms care about is that you use the site. If you could teach them that showing you content that makes you a reliably better person - in whatever way you want to define that - also keeps you using the site, you suddenly have the resources and technology of the world’s most powerful companies working to find more content that will do that. And as you do this more, you can refine your standards, so that the quality of content continues to rise, bringing you with it.

Suddenly, instead of a feed brimming with garbage, you have a legion of algorithms working tirelessly to pick the most nuanced, thoughtful, reasonable, and long-term-useful content from the morass and deliver it to you. You’ve gone from being collateral damage in the war on attention to purposefully using technology to improve yourself in lasting ways.

Before I go on and explain how to do this, I want to pause here because this is the deeper message of this essay: as new sources of information increase, we will be faced with the very real problem of sorting and prioritising it. For most of human history, we’ve managed this ourselves, but in some areas we’ve reached the limits of what we can reasonably sort 6. This puts us at a tipping point, where we need to increasingly offload the administrative burden of discovering, prioritising, and (increasingly) acting on 7 content to machine learning systems. If we do this without considering what those algorithms are optimising for, we risk handing a large part of our lives to systems not aligned with our terminal goals. Currently, they optimise for our attention and our ad-clicks, and this has given us fake news, political polarisation, and filter bubbles. Currently, we can still trick-or-teach them to show us content that both keeps our attention and fulfills some higher purpose of our own. This is only because time-on-site and consuming useful content are not mutually exclusive. However, the natural descent into clickbait that arises out of the competition for attention should remind us that optimising without thinking about second-order effects inevitably leads to unforeseen consequences. We want algorithms to decrease the time we spend on mindless admin. We need not be mindless in how we get there.

A guide to changing your algorithmic reflection

If you wanted to combat this, you might try some of the following (this guide mostly focuses on YouTube because it’s particularly well suited to long-form content that could lead to real, lasting improvements, but similar actions on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter etc. will also work):

1. Decide on a direction

Start by deciding on exactly what aspect of yourself you want to improve. This can be pretty general to start because the algorithms will naturally find and explore relevant material for you. All you have to do is make sure you only engage with content relevant to the part of you that you want to develop.

For me, I wanted to learn much more about machine learning and mathematics. I wanted to teach YouTube to find the most useful content about these topics. To keep this separate from my everyday YouTube, I created a new Google account and vowed to use it only for videos that would help me learn more about what I care about. To take away the hassle of remembering to switch between Google accounts, I set up a FireFox container (for Chrome users, this plug-in appears to do something similar, but I haven’t used it). Firefox containers keep all your log-in information separate for different accounts on the same website, like this:

Note how each instance of YouTube is giving me different recommendations, with the middle one giving the most relevant ones to machine learning. Now you can keep your different online personas separate!

2. Reset the algorithms

If you don’t want to create a new account, or you want to keep your current one, you can reset what the algorithms suggest for you by deleting some or all of your search and watch history. Simply head here, select ‘Delete Activity by’ and type in the keywords or time interval you want gone.

3. Bonus - browser plugins that make the internet far better

- DF YouTube (Firefox) optionally blocks sidebars, feeds, comments, suggestions at the end of videos

- uBlock Origin (Firefox, Chrome) has long been my ad-blocker of choice. It far exceeds AdBlock

- StayFocusd (Chrome) is great at blocking websites when you want to focus

- Wikiwand is not well known but deserves to be. If you use Wikipedia as much as I do, you’ll appreciate the look and feel this adds!

Go Forth

Algorithms discover, surface, and propagate the content we see. This is unavoidable - desirable even. Everything you interact with on social media is teaching some system what you and people like you are interested in and value. The reflection of ourselves we currently see in the algorithms and on our feeds is distorted, muddied by what gets clicks. Remove the silt, let the waters settle, then move forward with purpose and direction!

Cover Photo by Alexandre Debiève on Unsplash

-

Am I really going to throw in 2 CGP Grey references in such close proximity? Yes. Watch this video for a basic overview of how algorithms and your feed play together ↩

-

For the Bayesians here: think of the people ‘like me’ (and my age and demographic info) as giving a prior probability for what I’ll like, and each piece of content I engage with as updates that refine the model ↩

-

I view the process of removing yourself from this ocean as a separate (and also incredibly important) venture. For more, Cal Newport’s new book, Digital Minimalism is a great start ↩

-

I made a dummy account using my real age and demographic, then logged in to YouTube to see what I’d be shown ↩

-

Seriously, try having a look at YouTube videos with less than 100 views, they’re generally terrible ↩

-

Do you know anyone who is happy or even content with the amount of email they’re currently receiving? ↩

-

Think the automatic replies in Gmail or Google Calendar scheduling in your flights after you get your ticket confirmation email ↩